Luigi Guffanti 1876

Enzo Sisto 24 september 2025

The Encounter with Carlo Guffanti Fiori

There are places in Italy that seem suspended in time, capable of containing within themselves the strength of an age-old tradition and, at the same time, the vitality of a present that never ceases to renew itself. Arona, overlooking Lake Maggiore, is one of these places. Here, among the winding streets that climb toward the old town and the scents drifting from the lake and the mountains, stands a true temple of taste known to every cheese enthusiast: Luigi Guffanti 1876.

Crossing the threshold of this house does not simply mean entering a business: it means stepping into a world made of memory, knowledge, and sensitivity. It means finding oneself before shelves that tell the story of generations, where milk becomes culture and time is as essential an ingredient as salt or rennet.

At the center of this universe is Carlo Guffanti Fiori, a descendant of the family that for almost one hundred and fifty years has carried on a unique craft: not only producing cheese, but raising cheese. This very definition is striking and surprising. It is not about raising animals, but about accompanying cheese in its growth, from the moment it leaves the mold until, fully matured, it is ready to tell its story through taste.

Meeting Carlo means coming into contact with a man who has chosen to dedicate his life to this mission. Elegant and kind, with a smile that betrays his passion and eyes that light up whenever he speaks of milk, molds, and maturation, Carlo is much more than an affinatore: he is an ambassador of Italian cheese to the world, a custodian of dairy knowledge unafraid of confronting innovation, while remaining deeply rooted in tradition.

Our day with him was an unforgettable journey. Not just a company visit, but an itinerary made up of experiences, tastings, stories, and lessons that turned into a true masterclass on cheese. From the visit to the aging cellars to the explanation of coagulation, from the tasting of great erborinati to the dinner prepared with meticulous care, every moment was a piece of a larger mosaic: that of the culture of taste, lived with authenticity and without compromise.

Visiting the Company and the Guffanti Philosophy

Arriving at the headquarters of Luigi Guffanti 1876 means entering a microcosm where the past dialogues constantly with the present. The first impression is one of order and sobriety: a structure that does not flaunt luxury, but exudes authority and history. It is like standing before a living archive, where every detail—from the bricks of the cellars to the shelves laden with wheels—tells part of the long adventure of the Guffanti family.

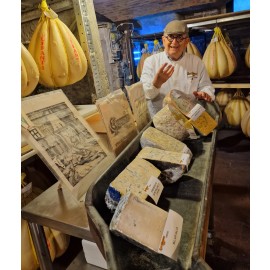

We were welcomed by Carlo Guffanti Fiori himself. He does not have the attitude of someone reciting a script, but the spontaneity of someone who lives and breathes this place every single day. Wearing the white coat of the affinatore and his cap, he immediately invited us to follow him. “Here cheese is not simply produced,” he said, “here it is raised, it is accompanied. That is why we call ourselves allevatori di formaggi—cheese raisers.”

The definition seems poetic, and indeed it is. But listening to Carlo makes it clear that these are not just words: it is a true approach to the craft. The cheese raiser does not merely control a process but interprets it, guides it, enriches it with sensitivity and experience. It is a work of constant attention: turning the wheels, monitoring humidity and temperature, observing the molds, even listening to the sounds a wheel produces when tapped with the fingers.

As we walked through the rooms, Carlo recounted the family’s history. It all began in 1876, when his great-grandfather Luigi Guffanti had the intuition to age Gorgonzola in abandoned silver mines in the Valganna. Those galleries, with their perfectly stable microclimate, were ideal for giving life to a superior quality erborinato. It was a stroke of genius: time and nature did the rest.

Since then, the company has grown, expanded, and traveled the world, but without ever betraying the heart of its identity: respect for milk, for manual craftsmanship, and for time. “Today everything rushes,” Carlo observed, “but cheese cannot rush. It needs slowness. That is its strength.”

The Guffanti philosophy is based on three pillars:

- Time – No shortcuts, no industrial compromises. Every cheese follows its natural rhythm.

- Place – The cellars and their microclimates are as much part of the recipe as the ingredients. It is no coincidence that some wheels aged here develop aromas impossible to reproduce elsewhere.

- Care – Cheese is alive, and like any living organism it must be observed, listened to, nourished. Every gesture, from turning to brushing, has a precise meaning.

Carlo accompanied us with enthusiasm, alternating family stories with technical explanations. He is an tireless storyteller: every shelf becomes an opportunity to talk about a DOP, every wheel tells its own story, every mold has a personality waiting to be revealed.

What stands out in particular is the cultural dimension. Here we are not only speaking of food production but of Italian cultural heritage. The company is not a museum, yet it behaves like one: preserving, protecting, handing down, while at the same time keeping alive what it safeguards.

The result is a rare balance: a place where business is conducted—since Guffanti exports worldwide and is a point of reference for haute cuisine—yet one that still breathes like an old-fashioned bottega.

When we left the offices and descended into the cellars, it felt like entering a temple: before us opened the kingdom of the wheels, the beating heart of the company.

The Aging Cellars: Between Aromas, Molds, and Silence

Descending into the cellars of Luigi Guffanti 1876 is like changing verb tense. Outside, the present flows; down here, everything speaks in the imperfect: what “was,” what “was becoming,” what “was maturing.” The air is cool and dense, humid enough to fog up glasses at the first step. The nose immediately perceives a mosaic of notes: warm bread, dried fruit, wet stone, hay, butter, and a hint of ancient cellar—that unique scent only living places, frequented daily by wheels and hands, can release.

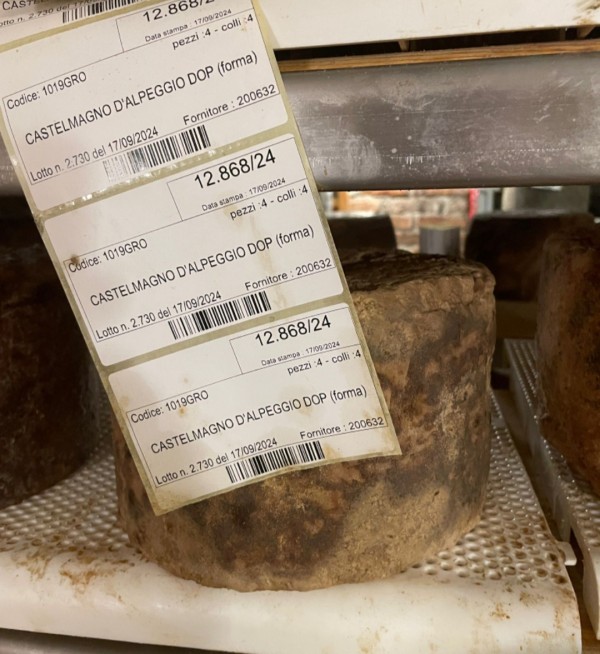

The corridors open like small naves. On one shelf, disks of Comté in sequence, each with its cartouche and rind markings; on another, darkened cylinders of Castelmagno d’alpeggio DOP, browned by time and etched with a rugged rind that speaks of the mountain. Further on, the large, dark drums, almost velvety, that evoke ancient Sardinian cheeses or cooked pastes with long maturation: fascinating, resembling giant black truffles. Every wheel is recorded, labeled, traced. Nothing is left to chance: the Guffanti method is as rigorous as a musical score.

Carlo walks ahead of us and, with a simple gesture, caresses the rind of a wheel as one would greet an old friend. His fingers know that language: they understand when it is time to turn, to brush, to oil. He explains how temperature and humidity are “structural” parameters, but the difference is made by the hands and the ear: the ability to tap the cheese and hear its sound, to read the rind like a map, to interpret the bloom of molds like a season.

The shelves—wood, steel, stone—host the lactic geography of Europe: Piedmontese and Lombard valleys, French mountains, plains where the milk is rich and round, highlands where it arrives leaner but more aromatic. The impression is that of an archive of taste. There is the order of libraries: shelves, tags, positions. And there is the voice of books: each wheel sings its own plot of proteins and fats, of lactic bacteria and seasons.

In front of a row of imposing wheels, Carlo pauses and speaks of “vertical time”: maturation is not just duration, it is depth. A six-month-old cheese is not simply “older” than a three-month-old one: it is an organism that has lived more experiences. It has lost water, concentrated flavors, rebalanced acidity and sweetness, developed tyrosine crystals—an amino acid component of casein—that crunch between the teeth like dry snowflakes. It is in this language that the affinatore moves: with time as an ingredient.

In one wing of the cellar, we stop at the family of blues. The cut wheels show distinct veins, turquoise and gray-green, like maps of an archipelago within the paste. Carlo explains the need for oxygen, the micro-piercings with needles that allow the colonies of Penicillium roqueforti to breathe and work, the importance of calibrated salting to tame the proteolytic energy of the molds. It is a balance: too little oxygen and the blue remains mute, too much and it becomes aggressive; too little salt and the cheese collapses into acidity, too much and it dries the palate.

The silence is broken only by the sound of soles on damp terracotta and the murmur of explanations. The light is warm and unobtrusive; you can sense it in the photos you took: the texture of the bricks, the gleam of labels, the white of coats. Each shot brings home a piece of this industrious calm. There is nothing theatrical in the scenic sense; yet the whole is spectacular. Here beauty is not an aesthetic game: it is the visible form of quality.

Leaving the cellar, the impression is of having crossed a laboratory of food alchemy. We climb back toward the light with a new awareness: what we eat is the result of a pact between man, milk, and environment. A fragile pact, one that needs people like Carlo to be renewed each day.

The Masterclass: Coagulation, Erborinati, and the Art of the Cheese Raiser

The masterclass with Carlo Guffanti Fiori was the most educational and, paradoxically, the most emotional part of the day. It was not a lecture but a guided conversation, where every technical explanation was grounded in the lived experience of the cellars and—above all—in the palate. Because here, cheese science is always at the service of taste.

We began with coagulation, the moment when milk becomes curd. Carlo clearly distinguished three major families: presamic coagulation (with rennet), lactic coagulation (through acidification), and mixed forms. The first, predominant in hard and semi-cooked cheeses, exploits enzymatic action (chymosin and pepsin) to aggregate casein micelles: the curd is compact, retains fat and part of the whey, tolerates energetic handling (fine cutting, heating at high temperatures), and leads to elastic pastes suitable for long aging. The second, typical of many goat cheeses and fresh cheeses, arises from acidity produced by lactic bacteria: the curd is fragile, watery, and must be handled delicately, yielding friable pastes with clean, lactic flavors. The mixed forms combine the two dynamics, creating an intermediate range that allows great stylistic freedom.

Carlo insisted on a crucial point: milk is never neutral. Species (cow, sheep, goat, buffalo), feeding, season, the life of the animal—everything changes the balance of fats, proteins, and minerals. And inevitably, everything changes the work in the vat and later in the cellar. A true cheese raiser does not impose a mold: he interprets, day by day, as a pianist adapts to the touch of a different piano.

We then moved on to the erborinati, the beating heart of the Guffanti tradition. Here the score includes one more player: molds of the Penicillium genus, especially roqueforti. Inoculated in the milk or curd, they remain latent until—during aging—they receive oxygen through piercing. At that point they grow, opening veins and eyes, releasing enzymes that break down fats and proteins, generating unmistakable aromas: pepper, walnut, chocolate, undergrowth, bread crust. The intensity depends on environmental management: humidity, temperature, salting, frequency of piercing, density of the paste.

The tasting table of the masterclass was a blue-toned palette: San Carlone di capra, Grevenbroecker, Buffalo (an erborinato made with buffalo milk), Shropshire with vegetable rennet and traditional Shropshire, San Carlone al caffè, and finally a Gorgonzola DOP piccante aged 250 days. Seeing them aligned—as in your photo in the cellar, with white labels on the cut edges—was like observing variations on the same musical theme: same structure, infinite modulations.

- The San Carlone di capra is a masterpiece of balance: the texture of goat’s milk, leaner and with smaller fat globules, gives a drier structure, while the blue contributes fine spiciness and a touch of citrus zest.

- The Grevenbroecker, of Flemish tradition, has “architectural” veining: wide eyes, almost like a Gothic cathedral, and a long, slightly tannic aromatic profile.

- The Buffalo surprises with its sweetness: the richness of buffalo milk softens the spiciness, delivering sensations of cream and cocoa, indulgent yet not cloying.

- The Shropshire chapter opened the question of vegetable rennet. Carlo made no ideology of it: he explained that thistle or other plant rennets trigger a different proteolysis, stronger on certain fractions, capable of generating bitterness if not carefully controlled. When well executed, the result is a cheese with a marked identity, wilder in its aromatic spectrum. Next to it, the traditional Shropshire offered a contrast: more “classical” structure, amber coloring (from annatto), measured salinity, and well-drawn blue development.

- The San Carlone al caffè was the alchemical element: the encounter between roasted notes and blue spores was not a gimmick but a dialogue. Coffee evoked bitter cocoa and licorice; the molds responded with dried fruit and a backdrop of lactic fermentation.

- The finale was entrusted to the Gorgonzola DOP piccante – 250-day reserve: a monument. Compact paste, dense veining, perfectly integrated salt, a persistence reminiscent of walnuts, black pepper, and dark chocolate. This is the kind of cheese that defines the memory of a place.

The masterclass concluded with a small manifesto: the affinatore does not “add” flavors; he liberates those that milk and technique promise. Sometimes he does so with visible gestures (piercing, brushing, massaging with oils or wine); more often, he does so by choosing not to act: not to anticipate, not to accelerate, not to force. It is the art of subtraction, governed by competence.

Dinner: The Menu, Pairings, and the Direction of Taste

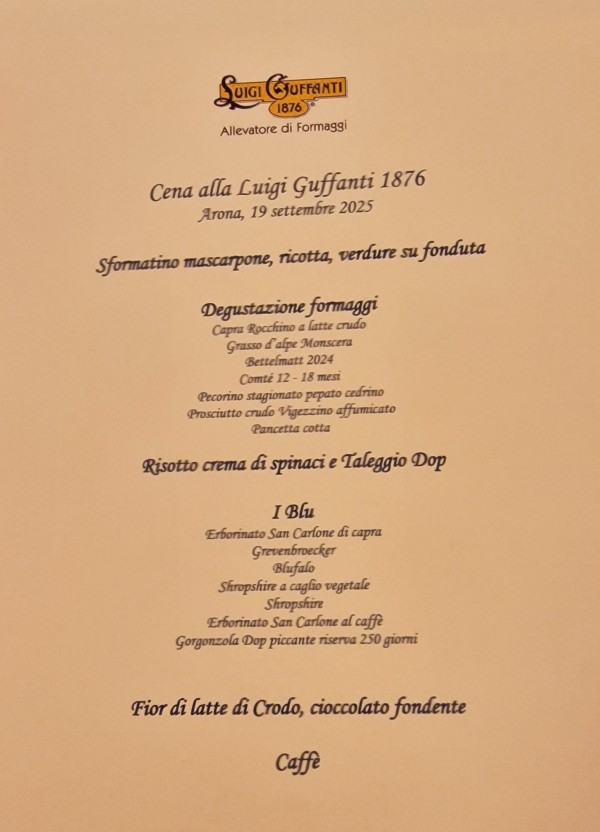

The day ended with a dinner that was, in essence, a continuation of the lesson: the same attention to detail, the same care in telling the story of the material. The mise en place was clear in your photos: cream-colored tablecloths, multiple wine glasses, breadsticks to cleanse the palate, and—at the center—the printed menu with the Luigi Guffanti 1876 logo and the date: Arona, September 19, 2025.

The opening was a comforting and precise starter: Sformatino of mascarpone, ricotta, and vegetables on fonduta. The dish immediately set the axis of the meal: lactic sweetness, softness, vegetal note, and that measured fonduta that bound without overwhelming. It was an invitation to calm, a way of aligning the senses to the right temperature.

Next came the cheese tasting with a board that also dialogued with cured meats. The list, printed on the menu and perfectly legible in the photos, was anthology-worthy:

- Capra Rocchino a latte crudo, elastic and clean, with that typical caprine streak redolent of herbs.

- Grasso d’alpe Monsera, fuller and more buttery, like a snapshot of summer pasture.

- Bettelmatt 2024, whose very name evokes the imagery of Ossola’s high pastures: yellow flowers, butter, hazelnut.

- Comté 12–18 months, balanced, with just a hint of crystals and a note of vegetable broth.

- Pecorino stagionato pepato cedrino, combining ovine punch with a dry, citrusy allusion.

Alongside the cheeses, two calibrated carnivorous touches: prosciutto crudo Vigezzino affumicato—a kiss of smoke, never invasive—and pancetta cotta, saline velvet. In the photo, the plate appeared arranged like a fan: golden-yellow triangles and slices interrupted by cubes of hard paste, accompanied by salad and citrus. An edible landscape, designed to guide the palate.

The risotto with spinach cream and Taleggio DOP was the bridge between whites and blues. The spinach added a polite chlorophyll that cleansed and refreshed; the Taleggio—melted but not overwhelming—enveloped the rice field with elegant richness. In the cup, you could see its creamy density, the spoon sinking effortlessly, a sign of a successful amalgam.

Then came the central act: The Blues. Here the mise en scène was truly scenic. In your photo, the white plate hosted wedges arranged like the hours on a clock; in the center, half a fresh fig and walnut kernels—the natural grammar of erborinati. It was an ancient yet effective gesture: sugar and fat, tannin and crunch, an unassailable pairing. The names were those of the masterclass—repeated from the card: San Carlone di capra, Grevenbroecker, Buffalo, Shropshire with vegetable rennet, Shropshire, San Carlone al caffè, Gorgonzola DOP piccante 250-day reserve—but here the light had changed. At the end of the day, with the senses educated, the profiles emerged with clarity: the vegetable Shropshire revealed its measured bitterness, the Buffalo spread like a savory cream, the San Carlone al caffè closed the eyes and resembled a savory tiramisù.

The wine pairing, immortalized in the photo held by the waiter, was MUFii – La Passitaia: a passito of bright amber color. Pairing it with the blues was not a luxury: it was intelligence. The wine’s sweetness softened the spiciness of the molds; its oxidative notes (honey, dried apricot, candied orange peel) embraced the dried fruit and cocoa tones of the cheeses. Each sip, after each bite, cleansed and relaunched, making you desire the next.

The dessert closed the evening in coherence with the place: Fior di latte from Crodo with dark chocolate. The cup you photographed showed the warm flow of chocolate over the milky white; the dusting of powdered sugar around it was an invitation not to take oneself too seriously. It was a simple and happy finale, a caress that returned to the primal ingredient: milk. The coffee, at the end, balanced the accounts and restored measure.

The dinner, overall, was a direction of taste. No exercise in power, no unnecessary overlays: the menu served to show the truth of the products, not to disguise it. This is the Guffanti signature: artisanal precision, contemporary reading, absolute respect for the material.

Carlo Guffanti Fiori: The Master Artisan Who Speaks to the World

What strikes you about Carlo, first of all, is his calm energy. He has the stride of a host and the curiosity of a student. He knows how to tell stories gracefully, how to delve into technical detail without losing his audience, how to remain human even when speaking of enzymes or acidification curves. He is what in other crafts we would call a maestro di bottega: a person who knows how to do, how to explain, and how to transmit.

In the photos where he poses next to large wheels—cap, round glasses, white coat—his style is evident. His posture is open, his hands always in contact with something: a wheel, a knife, a label. These are not casual gestures. An affinatore who keeps distant from the product does not exist; and an affinatore who deludes himself into dominating the product without listening to it makes disasters. Carlo is always relating: speaking to us, he looks at the cheeses; touching the cheeses, he speaks to us.

His vocabulary is inclusive. There is never a self-referential “I”; there is a “we” that includes family, collaborators, the cheesemakers whose products Guffanti matures and enhances, the farmers behind the milk. He frequently returns to the concept of filiera: not as a buzzword, but as a chain of responsibility. If a cheese is great, it is because each link—from the grass to the final day in the cellar—has done its part with honesty.

There is also a clear educational vocation. The masterclass was not an exception, but the ordinary way Guffanti operates: guided visits, structured tastings, moments of dialogue with chefs, sommeliers, and enthusiasts. It is a way of making culture that does not pass through rhetoric, but through the senses. Knowledge here is chewed. And when something is chewed, it stays.

Another distinctive aspect is international curiosity—not abroad as escape, but abroad as dialogue. You can see it in the presence of non-Italian cheeses in the cellars and on the menu (the Comté, the Shropshire, the Grevenbroecker), brought to converse on equal terms with the great Italians. It is an identity choice: if Italy is strong, it is even stronger when it engages with others and learns to see itself from the outside.

This posture explains why Guffanti is seen as a point of reference not only for fine dining and quality distribution but also for those who study and tell the story of cheese. Here craftsmanship is not mummified: it lives, innovates, verifies. Sometimes they experiment (think of finishes with coffee or other “intelligent affinamenti” that do not betray the product’s matrix); other times they step back, because tradition has already found the best version. The compass is not ego; it is taste.

Finally, there is the ethical dimension of the work: respect for animals and producers, care for the territory, the choice of timings that do not stress processes. In a world that often confuses quality with storytelling, here the story is read in the hands and on the palate. And in the long run, this creates trust: the most precious currency in food.

Conclusions: Time, Care, and the Truth of Milk

The experience in Arona, at Luigi Guffanti 1876, was much more than a company visit. It was a journey into the grammar of taste, conducted with rigor and gentleness by Carlo Guffanti Fiori. If we had to distill what we learned into a few words, we would say: cheese is time, relationship, and measure.

Time, above all. The cellars teach that every action only makes sense when inscribed in duration. Coagulation can happen in minutes; maturation requires weeks, months, sometimes years. There is no industrial shortcut capable of replacing the patient work of bacteria, enzymes, and humidity. Modernity can help control, but it must never pretend to accelerate without consequences.

Relationship, next. Cheese is a pact—between those who produce the milk, those who work it, those who mature it, those who tell its story, and those who consume it. This pact implies trust and responsibility. It is wonderful that a company with Guffanti’s history chooses to make itself a “square” where these relationships happen: in masterclasses, in structured tastings, in the conviviality of a dinner where the products speak before the speeches.

Finally, measure. The erborinati are the paradigm: just a few millimeters more or less in piercing, a few grams too much or too little of salt, and the trajectory changes. The greatness of the affinatore lies in perceiving the right moment, in not taking a step too far or too short, in letting the material follow its path. It is the same measure we found in the menu: a calibrated crescendo, from the appetizers to the parade of blues, to the milky dessert that brought us home.

If today we speak of “cheese raisers” and not only of “affinatori,” it is also because of a crucial linguistic point: to raise means to take care. It is not a verb of control; it is a verb of responsibility. Carlo Guffanti Fiori—with his presence, his calm voice, his ancient and precise gestures—is the incarnation of this. It comes naturally to think that the future of quality cheese will pass from places like this: where memory is preserved, competence is exercised, and the desire to understand remains alive.

Stepping outside, the lake air refreshes and expands. In your pocket is the folded menu, in the photos the smile of the host, on your hands the memory of the scent of rinds and cellar. But above all, there lingers in your mouth a trail: a long note of walnut and cocoa, of dry grass and cream, of warm bread and wet stone. It is the trail that only great cheeses—and great places—know how to leave.

And so yes: “Dinner at Luigi Guffanti 1876, Arona, September 19, 2025” is not just a date printed on a card. It is a chapter of an Italian story that continues to be written every day, calmly, precisely, joyfully. A story worth telling—and worth living again.

CURIOSITY

Lorenzo 2005

There is a cheese that speaks of family even before technique: Lorenzo 2005, created for grandson Lorenzo and deliberately started in 2005. In the Guffanti household, every grandchild has had their own cheese—an affectionate gesture that becomes a rite of maturation. “Shall we wait for the wedding to taste it?” someone asks. No. Carlo takes a screw probe, pierces the rind with resolve, and extracts a small cylinder of paste; a few grains fall into my palm like gemstones. I place one on my tongue: an explosion of umami and emotion, profound yet bright. Carlo then reseals the tiny hole, using a little of the same paste to close the wound and let time resume its quiet work.

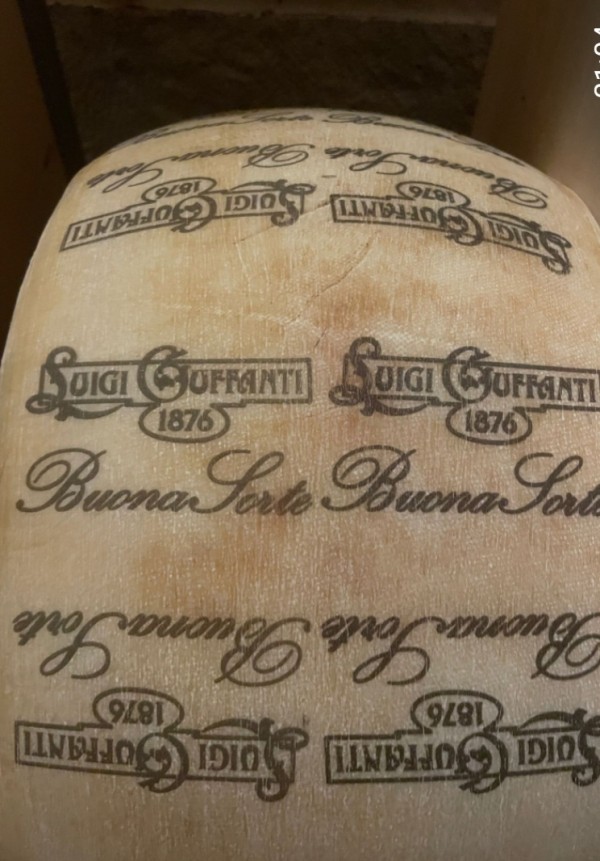

BuonaSorte 24 months

To enhance this cheese, Guffanti selected a producer from the lower Adda area who works with raw milk from animals fed exclusively on forage from that zone. Among the customs that remain unchanged is the cascinai dialect: they have always referred to their cheese batches as “sorte,” acknowledging that outcomes might be better or worse with a margin of chance.

Hence BuonaSorte: the name reserved for batches with excellent results. The special version developed by Guffanti strictly employs raw milk and—crucially—no lysozyme.

BuonaSorte Guffanti: good cheese indeed!

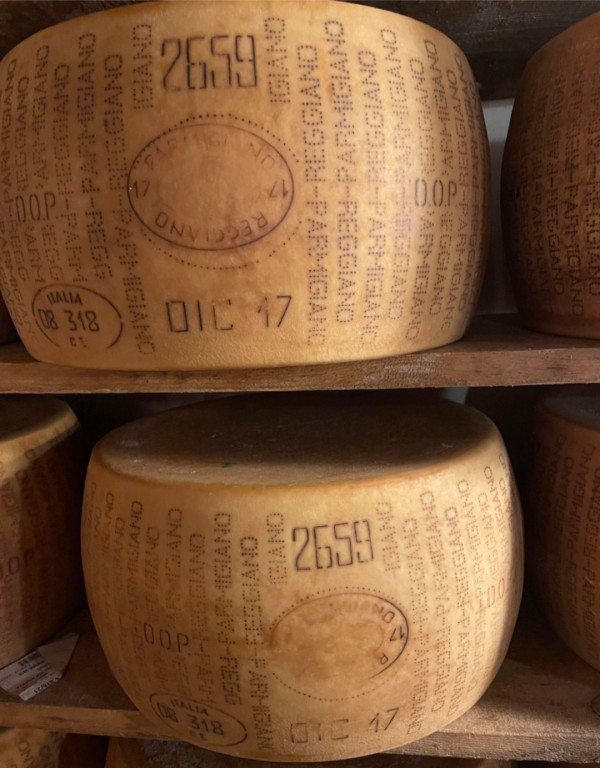

Parmigiano Reggiano "millesime 2016"

In the Guffanti cellars only four wheels of Parmigiano Reggiano 2016 remain, pictured alongside some from 2017.

A golden shard of the rarer vintage, crunchy with crystals, releases notes of dried fruit and concentrated broth. Such a taste deserves a great companion: an elegant Barolo Riserva or a 30-year-old Tawny Port. Together, they turn a fragment of cheese into pure emotion.

Castemagno DOP

Castelmagno is the only blue-veined cheese still made with an almost medieval method. Legend links it to Charlemagne, who, after tasting it, took it to France to be reproduced by monks. Today it is produced exclusively in the Val Grana (Castelmagno, Pradleves, and Monterosso Grana) and has held DOC status since 1982. The alpine pasture version, limited to a single cheesemaker, is a true rarity. Sadly, it is often sold too fresh: only after six months of proper aging does this cheese reveal its noble veins and exceptional character.

How should I express this? Tasting cheese at Guffanti is not eating; it is learning how to listen.

Enzo

Gerelateerde blogs

Delightfully Fishy Dry-Aged Treasures

Enzo Sisto 15 september 2023

The Finest Cut's Journey into “Fishy Dry-Aged Delights” Rui Gaudêncio fell in love with dry-aged meat during a trip to Portugal, and it led him to create "THE FINEST CUT".

Passion for wine and meat: BEEF & CO. B.V.

Enzo Sisto 18 februari 2017

Beef & Co. in Utrecht (www. rundvleesco.

The Burger born to match people

Enzo Sisto 7 maart 2021

The Urban Share Steak Burger, as the product's name says, was born as a burger to share. The ingredients are exclusively natural. Meat comes from suppliers previously selected according to the virtuous production of breeders, the level of food safety and the certifications acquired.